Posted by CHARLES lipscombe on 27/04/2020 02:48:00:

… believed that seasoning castings made from cast iron was necessary to relieve stresses and avoid distortion after machining. … many ideas on exactly how to do this, some of doubtful merit…

If seasoning was ever necessary, was this because of the grades of CI available at the time, and possibly their method of production? Therefore not necessary now?

Does Andrew or anyone else ever season CI castings, i.e.is seasoning relevant nowadays? Especially for the size of castings we are likely to encounter in model-making activities.

… what sort of temperature/time cycles are we talking about?

Chas

A complicated subject Chas!

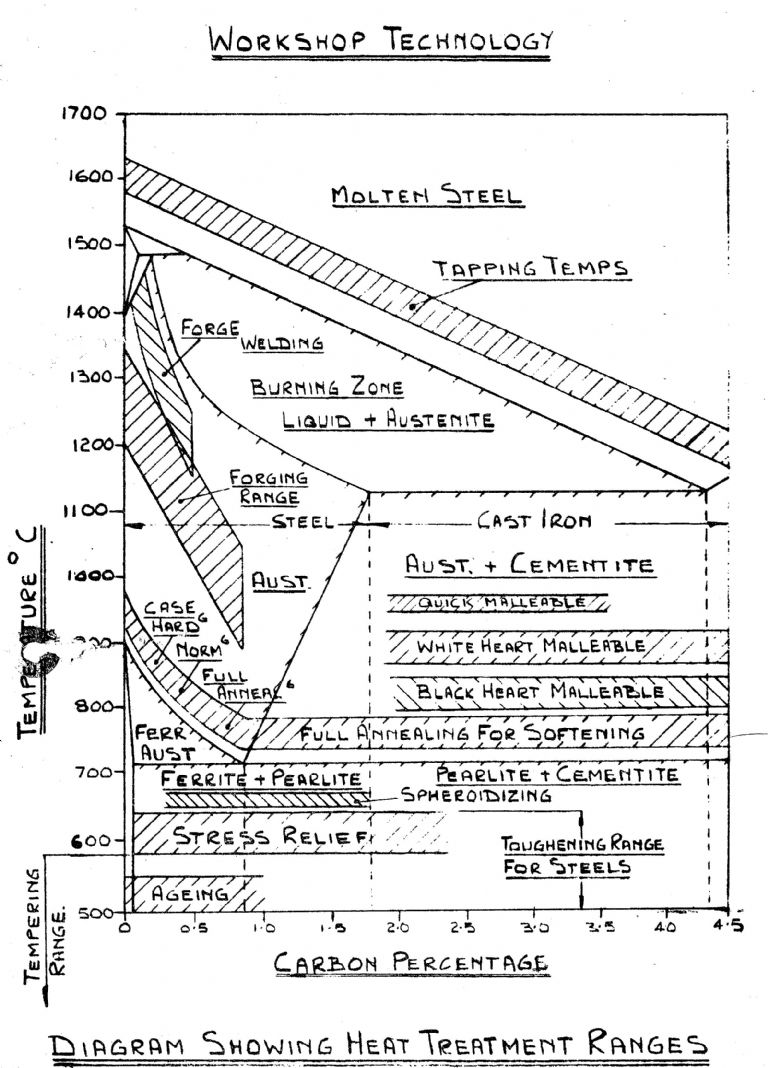

'Cast-iron', isn't one material. Broadly, it's Iron with a lot of Carbon, but in the past it also contained Silicon, Phosphorous, Sulphur, Manganese and other muck. Impurities change the properties of cast-iron significantly, and – before chemistry fixed it – where ore came from mattered.

Before the industrial revolution top-quality iron came from Sweden because they have large deposits of pure Iron ore plus wood for charcoal, pure Carbon. British ironmasters struggled at first because our ores are mixed and they tried to swap Coal for expensive Charcoal. Unfortunately coal also contains many local impurities. Any success seemed like magic!

However, with a simple furnace impure cast-irons can be melted and easily moulded. Bit hit & miss, but some areas were able to make useful iron with local characteristics. Scottish iron was better than Lancashire iron for some purposes and vice-versa. Making metal was more art than science.

During the 19th century improved chemistry found the impurities. Sulphur and Phosphorous are both very damaging and chemists showed how to remove them from ore and coal. Knowledge replacing skill and folklore.

So, rather than relying on the furnace master, he got a better furnace, materials, and operating guidelines. A large enterprise would have a chemist testing iron during the melt to guarantee consistency. The quality of cast-iron improved enormously. Science displaced guessing.

Nothing is ever simple! Many jobbing foundries bought in metal, including scrap, and did practical casting work of the cheapest possible kind. Sash-weights can made with almost zero skill using left-overs, perhaps poured cool without bothering to remove slag, and then hosed down to get them out quickly. Today old sash-weights are notoriously poor quality with an exceptionally hard skin.

Structural and ornamental iron-work and machine parts got more care. However, it's fairly easy to get manual casting wrong. Experts taking care and getting the timing spot on do well, less reliable from the 'B' Team zonked out at shift-end, or when management rush stuff out the door. Blow-holes, slag inclusions, shrinkage, cavities, chilling, heat stresses, etc.

Stress inside large mouldings due to uneven cooling was a major problem in the 19th century and still can be. Machining stressed castings can cause the whole thing to warp, very bad on a lathe or milling machine! Large complex castings seem more likely to warp than small.

One solution is to rest precision castings outdoors for a year or three. Fairly obviously, this is another hit and miss method, but – because it's expensive – it became associated with quality. Slow cooling in an oven works too. Peeing on the casting is lore, not science.

Science hadn't done with cast-iron. Iron was studied to get a solid understanding of how to get specificied results. Repeatable hardness, machinability, toughness, brittleness, stainless, etc. Now thousands of different alloys are available.

Cast-iron's main advantages are cheapness, moulding, machinability, compression strength, and absorbing vibration: excellent for making machine tools and engine blocks. Having to wait months for castings didn't appeal to early car-makers or US machine tool firms. The US developed cast-irons that didn't need to be seasoned. This is Meehanite, about 30 variants, used in a defined way in an upgraded foundry rather than poured by eye.

After 1935, seasoning cast-iron hinted the manufacturer was old-fashioned! Unfortunately too often true: in the 1920's buying a British lathe meant waiting a year or more for delivery, while American machines could be had in weeks. Some kind of strange conservatism caused British firms and workers to favour waiting for machines built to last 60 years or more, missing the point that 1995 would be a different world. Move with the times or else!

Today, cast-iron is all over the place. At one end it's a state-of-the-art engineering material. At the other, crude foundries casting cheapo street furniture, weights, and novelties. In between, almost anything else depending on need. The decision to season or go clever mostly depends on cost. It depends on some mix of foundry capability, run size, and when the customer needs the castings. Seasoning doesn't necessarily indicate quality, rather it's just a tool.

Warping isn't a problem I've found on my Chinese tools and I doubt they had any special treatment. Although the castings are rough, they're OK where it matters. Anyone found a warped bed on any machine, new or old?

Dave

Edited By SillyOldDuffer on 27/04/2020 12:38:14

Roger Whiteley.