Posted by Anthony Knights on 02/05/2022 13:04:36:

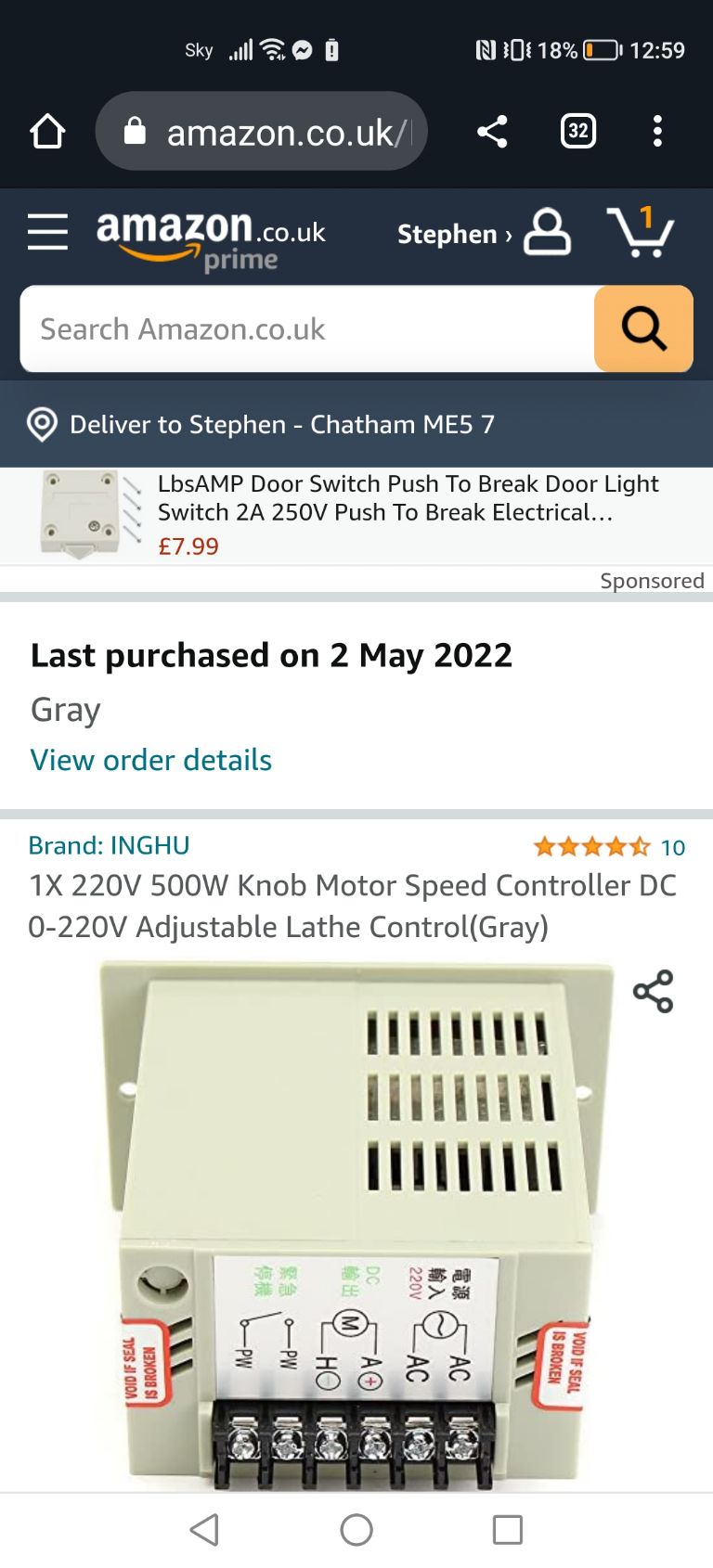

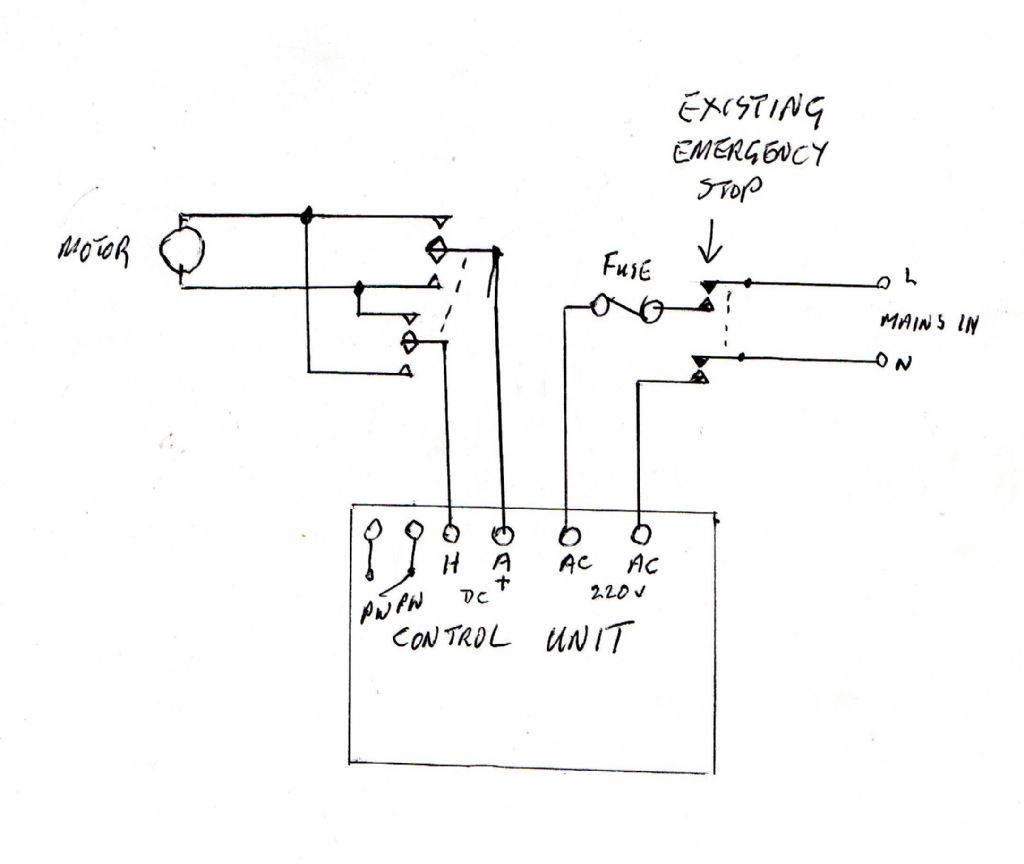

The motor on my Clarke CL300 lathe is a 180volt DC permanent magnet brushed motor, rated at 350(chinese) watts.The control unit shown is rated at 500 (chinese) watts and works fine on my lathe. There is an internal adjustment for the output voltage. I fitted the pcb in the original lathe control box. While this voids any warrentry, for £20, I thought it was worth the risk. This is only a temporary measure as I already have a 3phase half horse power motor with inverter which I am in the process of fitting now. Keeping the lathe running with this cheap control box enables me to make the bits necessary for the conversion. Interestingly, the 1/2 HP motor is physically twice the size of the DC motor and they are both in the 350watt range (1hp=746 watts). It must be the difference between Chinese and British watts.

There's absolutely no difference between Chinese and British watts!

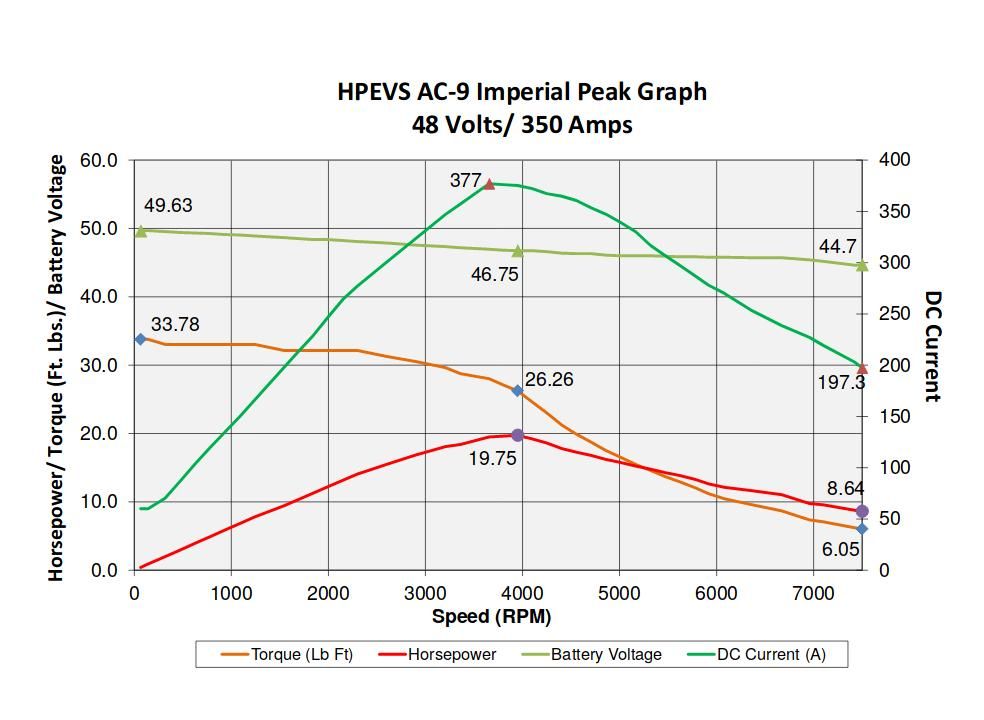

Confusion arises because it's not always clear what's being measured, which can be exploited by salesmen, and I suspect most motor users don't understand how the number of watts consumed by a motor varies with load. It's complicated, and is best understood by looking at a graph, like this example:

If you think a 500W motor is a 500W motor in all circumstances you are wrong, wrong, wrong. In the example above, a DC motor:

- The motor is rated at 48V and 350A. It's a 16.8kW motor (input watts)

- The power supply should produce 350A continuous, but note the motor actually draws 377A at 2500rpm. The designer should overrate this motor's power supply by at least 10%, but providing a 400A supply doesn't mean the motor is magically able to take 19.2kW input without overheating.

- The 16.8 kW input only occurs at just under 4000rpm, and it coincides with the motor's peak output, which is 19.75HP (about 14.7kW)

- All bets are off when the motor is run at any speed other than just under 4000rpm. At about 1800rpm, the output is only 10HP (7.46kW), and the output also drops to 10HP at 7000rpm.

- The graph is drawn for whatever the manufacturer considers normal operation. The actual maximum input and output powers that can be taken are only limited by the motor's ability to get rid of the heat without melting the insulation. If the motor works in bursts and has time to cool off, it can deliver much more power than when operated continuously. This is why hobby machines tend to be fitted with physically smaller motors than the industrial equivalent. The expectation is that hobby machines will be worked relatively lightly and in short bursts. It's easier to overload a hobby motor with long hard cutting than an industrial motor.

- The graph doesn't show what happens toi input and output power during an accident. Worst case, if the motor is stalled, the output watts spike, then drop to zero, while the input watts go through the roof, potentially damaging the motor and blowing the power supply up unless it's clever enough to shut down, or has a fast-acting fuse.

Simply put:

- when choosing a lathe, the owner wants to be told output watts, but salesmen like to quote input watts because it's a bigger number. They're also prone to not mention the power is only expected to be taken in short bursts. Unless otherwise stated in the specification, hobby machine owners are wise to assume their motor has a low duty cycle, that is it can do hard work but only in short bursts with time allowed to cool down. Heavy handed owners should note electric motors can and will exceed it their ratings, and this risks popping the power supply.

- when choosing a power supply to match a motor, the owner needs to know the motor's input watts; knowing the output doesn't help much. The power supply should provide at least the input stated on the motor plate, plus an overload allowance. Most of the time, hobby lathe power supplies are run well under their maximum, so the allowance can be low, keeping costs down. But if you're a heavy handed accident-prone operator in a busy workshop, it would pay to allow more, say 30% more than the motor plate. But in doing this, remember a big power supply is more likely to burn out the motor and cook the machine's wiring than a small one.

If the size of the motor and power supply on a hobby lathe are a constant worry in your workshop, you probably have the wrong machine. What's needed is either a bigger hobby lathe, or a professional machine rated for continuous hard work. Don't expect a lightly built hobby machine to last long doing piece-rate production work! Although capable of accurate work, hobby machines aren't go-faster metal munchers!

Dave

Steve Lang.