Andrew,

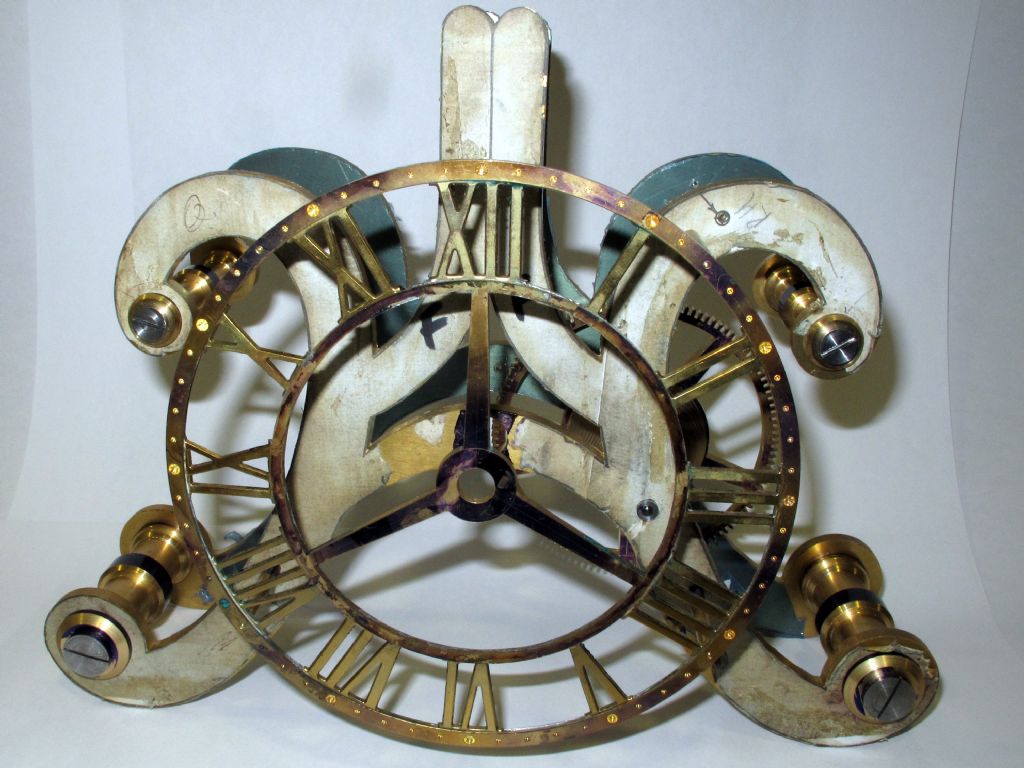

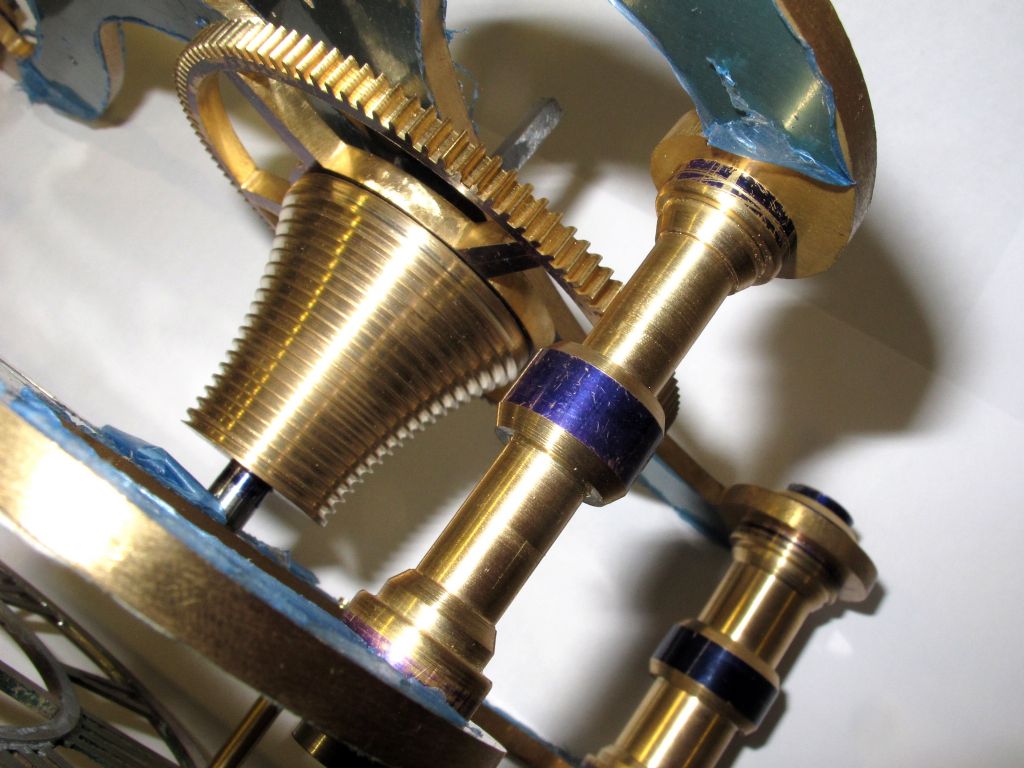

The Strutt is an interesting clock. I have the Bill Smith book on that one, and I have seen several completed clocks, some original and some made from the Smith instructions. Smith's book refers to the photos of a Strutt in Royer-Collard's book "Skeleton Clocks", but I see better photos of a wider range of Strutt & Wigston epicyclic clocks in Derek Roberts' book "British Skeleton Clocks" (Wigston was an engineer, and business partner of Strutt, so I imagine Strutt was the designer, but commercial manufacture was arranged by Wigston). I have seen instances of completed Strutts at verious ME exhibitions, and I think I recall seeing one a couple of years ago in the collection of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, held in the Science Museum. The interesting part of the machining of the Strutt is the cutting of the internal teeth of what Smith terms the ring gear.

I built a Wilding 16th Century one-handed clock with a verge and foliot escapement, as it was serialised in the Horological Journal in the late 1970s. I can still remember quite clearly the moment I got it to run, so I can imagine your ow joy with your current clock. I have a Widling Congereve almost clomplete, on the bench at the moment. I have built a number of skeleton clocks which originated from a Wilding design and are based on a pigeon timing clock. My plan was to start with the Wilding modifications and make some changes as I went through a series of those. The clock features a daisy wheel mechanism in place of the conventional motion work. After the first one, which was fairly close to the Wilding design, I made some significant departures from that design, so that the whole motion work is now quite different (although still based on the daisy wheel). The clocks also feature a prominent platform escapement, so I have had to learn how to deal with issues concerning springs and rating. Other parts of the original design have now been progressively modified, so that the whole thing is now rather different. That was the idea behind the 'series' of clocks, and although it has quickly taken me in directions I had not anticipated, I have enjoyed the journey. Along the way, I have been unable to avoid a constant stream of repairs to (mostly) longcase and wall-hanging clocks, and cuckoo clocks (which I find bring a smile…), all of which brought valuable (and sometimes hard-won) experience. And I have a design for a wall-hanging clock which I am almost ready to start making. That's if I can get the next 3 skeletons off the bench, and get the Congreve finished, polished and into its Perspex case. Interestingly, Wilding recommends polishing the pinion leaves, in the Congreve book (and others) but it is a technique explained in a number of general clockmaking and repairing books, so I am surprised it is not in the Great Wheel book. Polish; harden; re-polish (or at least clean after hardening).

I can recommend membership of the British Horological Institute, and its journal, as well as branch meetings of like-minded souls who are a constant source of good advice. They run good courses as well, at their headquarters. There is also a distance learning course which can be done at your own pace.

Marcus

Neil Wyatt.

Neil Wyatt.