Posted by BOB BLACKSHAW on 07/05/2021 09:43:25:…

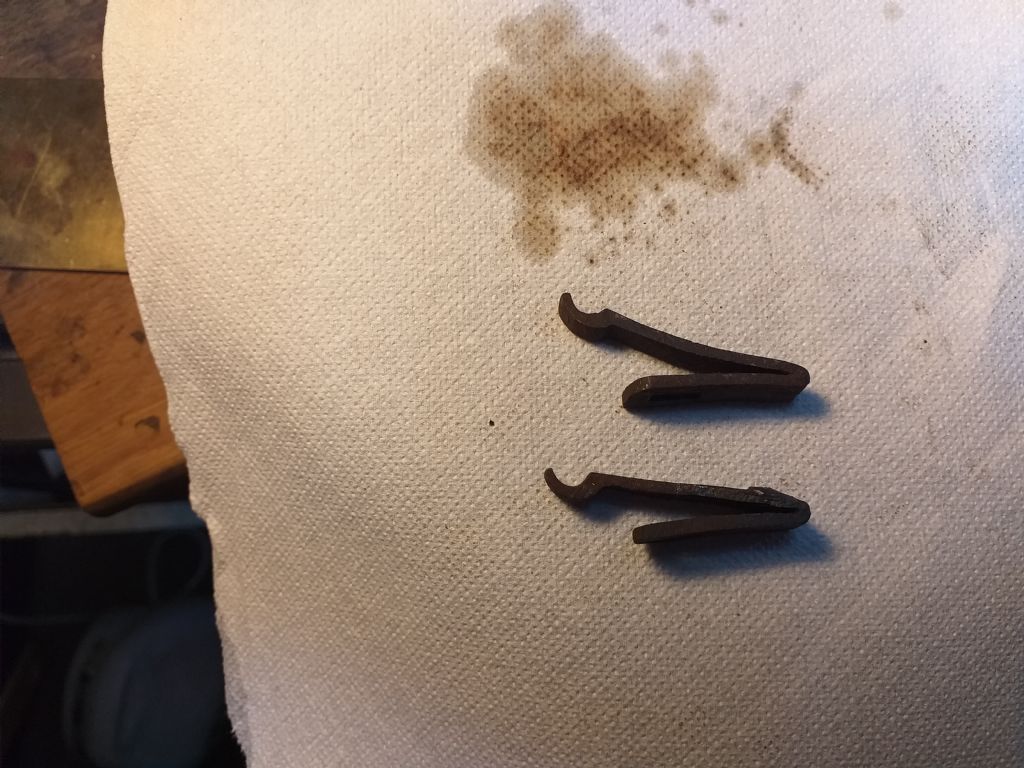

I brought some annealed spring steel, just over cherry red then in oil and then just starting to go blue then in water. the spring seemed ok , I bent it and the spring returned to size…

…half hour later the spring broke in half under no pressure,the spring broke on the base where no bend was made. Obviously getting the correct temperature which I'm not doing,

Bob

Don't despair, you're getting close!

I suspect 'just over cherry red' is too hot. What's meant by 'cherry red' isn't clear, I think it means glacé cherry colour as seen in dim natural light, not full daylight or an artificially lit workshop. May be easier to test temperature with a magnet. Steel loses magnetism when it's hot enough to quench. Try warming to dull red and seeing if a magnet is attracted to it. If not, quench, job done! Otherwise warm the spring to a slightly brighter red and test again.

I think the tempering temperature is too hot as well. Light straw yellow ( 205°C ) rather than Blue ( 340°C ). Wikipedia says 'tempering in the range of 260 and 340 °C causes a decrease in ductility and an increase in brittleness, and is referred to as the "tempered martensite embrittlement" (TME) range. Except in the case of blacksmithing, this range is usually avoided…"

I think the failure was caused by a crack started by cooling too fast from a high temperature, that developed in steel made more brittle, stressed and crystalline by too hot tempering. The spring might have been OK if it hadn't been tempered at all!

I learned something about quenching by watching 'Forged in Fire' on TV, which is like the 'Great British Bake Off' except Americans make historic knives and swords. Old springs are often used to make blades.

Even though the competitors are experienced, the quench often goes wrong. Blades stay soft, warp, and crack. Sometimes the metal is accidentally overheated enough to remove Carbon, converting the blade into useless mild-steel or worse. Rule of thumb, the smith has three attempts at quenching, after which the blade is scrap.

Cracking and brittleness often appear only during the brutal test phase – many a perfect looking knife shatters on impact.

Lesson learned: judging the right temperature for a quench is a little difficult even for chaps who have done it before; the right temperature has to be held steady for a certain time, and then cooled at the right rate. The whole item should be at the same temperature, not white hot in the middle and dull red at the ends. Cooling in oil is preferred because quenching in water is high-risk. Dithering and excessive haste are both bad! Interestingly, blades are often left untempered, but that may be because edge hardness is important in cutting tools. I think springs should be tempered.

There's nothing like doing this stuff to highlight the skill of early metalworkers! I mess up in a modern workshop full of decent tools, good materials, reference books, and access to forum expertise. They did everything from scratch, more like magic than technology.

Dave

Edited By SillyOldDuffer on 07/05/2021 10:43:34

JohnF.