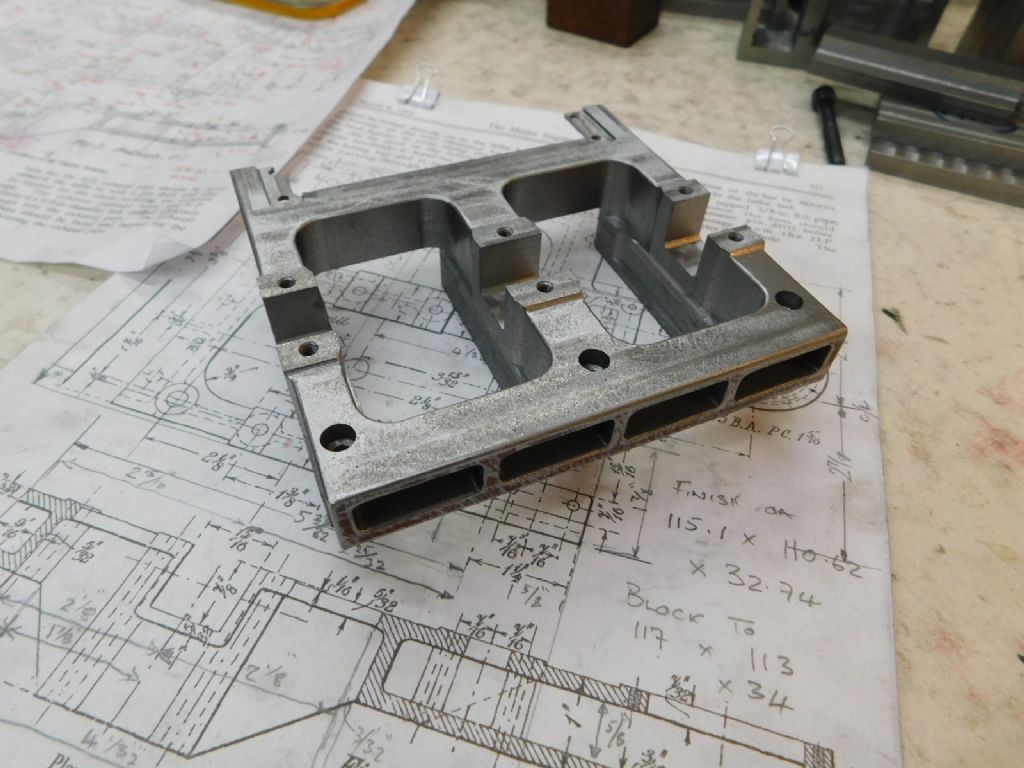

Had a look at my American Marine Engineering Book circa 1945.

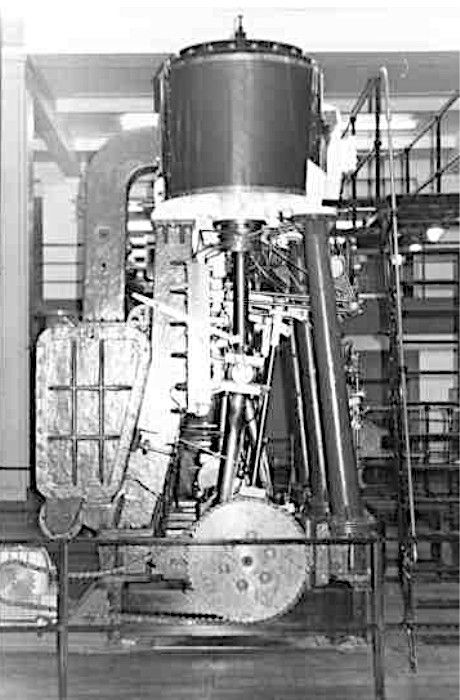

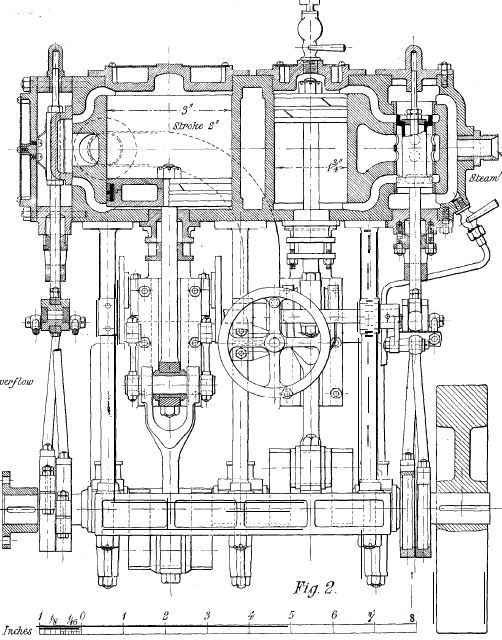

Volume 1 describes the US Maritime Commission Engine of 1940 in considerable detail. Quite interesting – it's the Triple Expansion Steam engine used to power Liberty Ships. Rationale almost engineering firm could make them, and reliable simplicity, not high-performance or fuel economy. Goes on to describe Woolf Engines, Lentz Engines, Steam Turbines and Maritime Diesels. None of these engines have flywheels.

However, Volume 2 has a section on vibration, and mentions flywheels as a way of controlling it. My idea of a flywheel is a hefty beast designed to store a lot of energy to deal with varying loads. Not how this book sees them. Small, if used at all, and intended to deal with resonances.

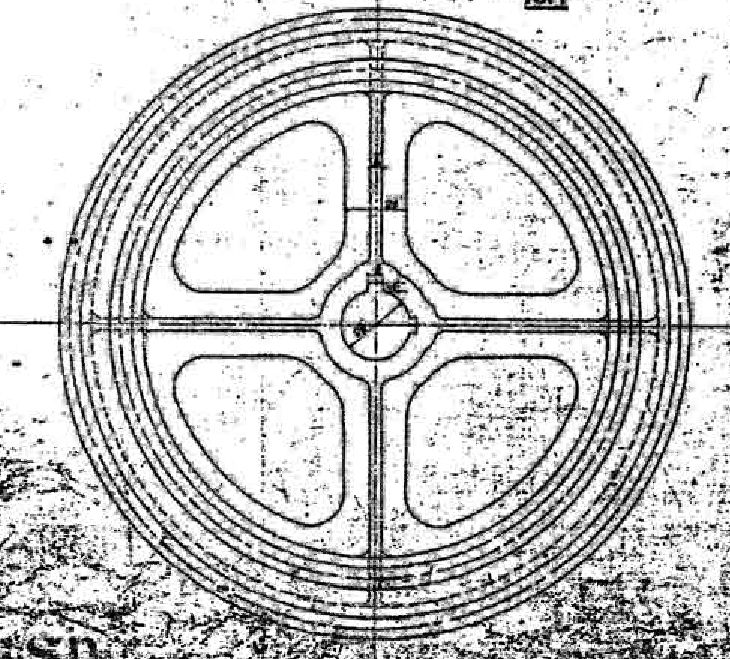

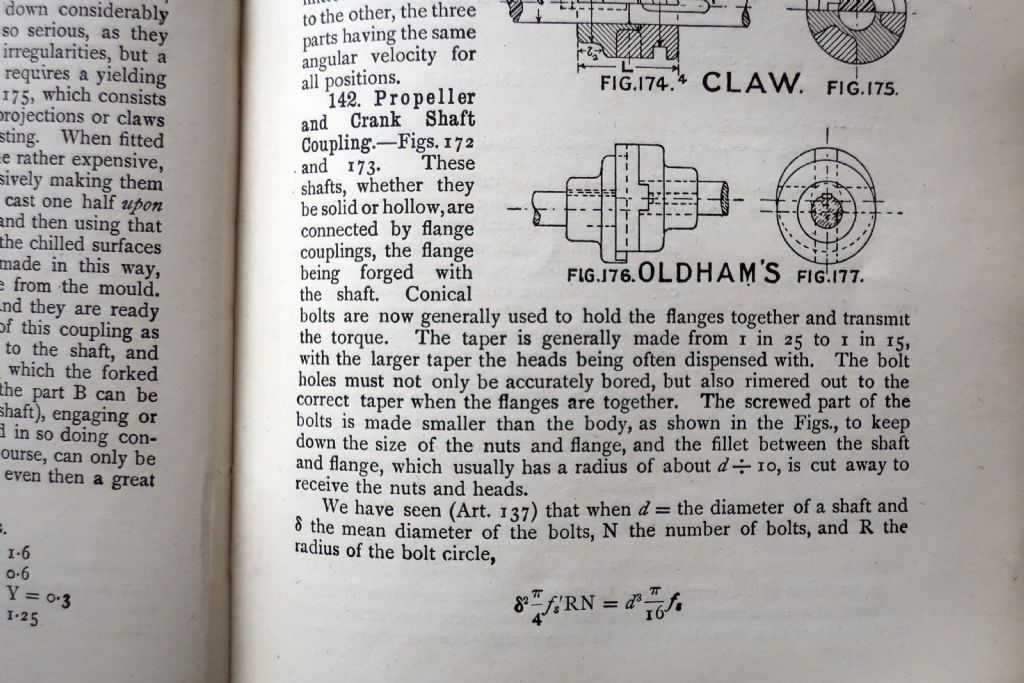

Looking at the engine plans in Volume 1, although they don't have separate flywheels, they do have heavily weighted cranks. Although the main purpose of the weights is balance, they would also have a flywheel effect, maybe sufficient to not need a separate flywheel at all. There are also features like the engine / propeller-shaft couplings that must act as small flywheels. The reduction gearbox on a steam turbine looks like a hefty flywheel – might take a turbine ship a few miles to stop!

Mill engines and pumps see varying loads and for them a big flywheel must be very helpful. Maritime engines don't have the same need for a flywheel because they deliver power into a steady load for weeks on end. I suppose a ship engine's worst nightmare is when the propeller dips in and out of the sea during a storm.

Dave

Ramon Wilson.

Ramon Wilson.